Posted by Van Wagner on 1st Sep 2016

Sixteenth & Seventeenth English Prison Life

Popular Culture: Sixteenth & Seventeenth English Prison Life

Life in prison during the early modern period was very complex, more complex than prisons of today. They contained all types of people from the very high classes to the poorest level. The prisons ran on a system of garnishes forcing individuals to pay for amenities. The facilities were much like a hotel. You could even leave under some circumstances. But unlike a hotel the worst rooms were like living in a barn. Prisons were places of contradiction; they allowed the rich to remain comfortable while making the poor live an even more brutal life. They were not places of punishment although that was inevitably a result. They were used as holding areas until payment was made to creditors or execution took place.

Prisons in particular lacked structure. They lacked this in physical and psychological contexts. In fact there was only one standard, the garnish. The time was one of much change, the middle ground between the old Middle Ages and the coming Industrial Revolution. It was here when different methods were under trial and error. Populations begin to shift to London. The old medieval city infrastructure was not ready for this rapid change. The chaos that ensued gradually forced this change. New technologies, such as the printing press, arose helping to spread information faster. This made it easier for change to occur. Former prisoners could spread their accounts faster by printing pamphlets. It was from these existing documents we find primary source accounts. A main change that occurred was to English prisons.

The following long passage describes the universe of the prison. It serves as an outline for the rest of this essay because it describes the many different sections of the prison. For example tobacco and drinking were common in prisons and they are mentioned here. The bad conditions are exposed as well as proving that prison life was more of a detention or custody rather than a form of punishment.

A PRISON

Is the grave of the living where they are shut up from the world and their friends; and the worms that gnaw upon them their own thoughts and the jailor. A house of

meagre looks and ill smells, for lice, drink, and tobacco are the compound. Plato's court was expressed from this fancy; and the persons are much about the same parity that is there. You may ask, as Menippus in Lucian, which is Nireus, which Thersites, which the beggar, which the knight;--for they are all suited in the same formof a kind of nasty poverty. Only to be out at elbows is in fashion here, and a great indecorumnot to be thread-bare. Every man shews here like so many wrecks upon the sea, here the ribs of a thousand pound, here the relicks of so many manors, a doublet without buttons; and 'tis a spectacle of more pity than executions are. The company one with the other is but a vying of complaints, and the causes they have to rail on fortune and fool themselves, and there is a great deal of good-fellowship in this[1]

This is a good place to examine the first part of the passage because the fellowship is described. In prisons close bonds were established between workers and staff. Close bonds were also formed between prisoners. It was very chaotic in the prisons. So they had more of a sense of community than compared to modern times. The next section shows how there was another side to the gambling and smoking. Prison also was a static place once your money ran out.

They are commonly, next their creditors, most bitter against the lawyers, as men that have had a great stroke in assisting them hither. Mirth here is stupidity or hardheartedness, yet they feignit sometimes to slip melancholy, and keep off themselves from themselves, and the torment of thinking what they have been. Men huddle up their life here as a thing of no use, and wear it out like an old suit, the faster the better; and he that deceives the time best, best spends it. It is the place where new comers are most welcomed, and, next them, ill news, as that which extends their fellowship in misery, and leaves few to insult:--and they breath their discontents more securely here, and have their tongues at more liberty than abroad. Men see here much sin and much calamity; and where the last does not mortify, the other hardens; as those that are worse here, are desperately worse, and those from whom the horror of sin is taken off and the punishment familiar: and commonly a hard thought passes on all that come from this school; which though it teach much wisdom, it is too late, and with danger: and it is better be a fool than come here to learn it[2]

The creditors are mentioned as being angry against the lawyers. This was because they failed to get them money and the criminals were hiding out in the prison. Prison was a game of deceiving time in order to create a distraction. The prisoners needed this distraction in order to escape this harsh reality. If you stared at the clock waiting to get out, then you would go crazy.

Prisons were an intrinsic part of the culture, associated with the bottom structure of the social ladder. If you do something good, you would rise to the top; if you did something bad you would fall to the bottom. In the present day, prisons are seen as the dead bottom. They act as the last stop. Being the final stop means one either rises again, plateaus, or ceases to exist. In 16th century England this was much different. Prisons were not as cut and dry as now. Each prison varied.

There was no uniform structure. In some cases prisons fit the terrible conditions one pictures, but this was just a small portion of the spectrum.

To understand the prison of the sixteenth century the prisons preceding this time must be examined. Scholars have contrasting views. Pugh argues that prisons in this time were for both holding and long term imprisonment.

Imprisonment in Medieval England, contrary to popular misconception, was punitive as well as custodial and coercive. In fact, the earliest mention of imprisonment, in the laws of Alfred, provides that defaulters on oaths or pledges be sentenced to forty days in prison at a royal manor. [4]

This is an interesting argument. It would mean that our current system of prisons began hundreds of years earlier than thought. Ireland though is skeptical of Pugh’s theory. He mentions that Pugh’s work is misleading and brings us to the wrong conclusion.

Pugh’s qualification may be misleading because it ignores the reasons behind early legislation on that subject. It will be argued that the rationale behind the punishment of defaulting debtor was not only a desire to make ‘yeild to his captor’s will,” but also that debt was viewed as a form of sin or social offence which merited punishment[5]

These two theories are answers to the question of how prisons functioned. They serve as guidelines. Proving that many different types of imprisonment did happen. It may be true that the prisons did have punitive punishment but it was not like what we think of punitive being in a modern day sense. The prisoners were kept to be reformed like today. Doing the crime and pay the time as no meaning in this era. It proves that there is no one answer.

These two theories are answers to the question of how prisons functioned. They serve as guidelines. Proving that many different types of imprisonment did happen. It may be true that the prisons did have punitive punishment but it was not like what we think of punitive being in a modern day sense. The prisoners were kept to be reformed like today. Doing the crime and pay the time as no meaning in this era. It proves that there is no one answer.

Looking at the timeline of dates I complied a pattern can be seen. Not much happened in terms of new laws at the start of the timeline. As the sixteenth century is approached more and more new laws are passed. This creates a ripple effect. When a stone is thrown into a pond it creates a ripple from the point of entry. The wave must reach the shore before the pond settles again. The pond is the prisons. This ripple continued through the sixteenth century created a turbulent time. No matter what the view of the scholar, the prisons all shared one thing. “For centuries in England, regardless of whether one was in jail for debt or crime, the charges of the jailer were exorbitant and continuous.”[6] So the prison of the Middle Ages was indeed an outdated beast that acted as a business in taking money from those guilty or not guilty. As evident from new laws, shown in the timeline, people wanted change.

Incarceration for a crime as evident from the previous scholars is a subject of great debate. Because of the Bridewell prison I feel that punitive punishment imprisonment did not exist in the way we think of prior to the sixteenth century. The majority of prisoners were people in debt. The Goal (jail) existed to force debtors to pay back what they owed. “Two of the commonest causes of imprisonment were debt and assault.”[7] The debtors were held until they paid back what they owed.

In a passage by author and prisoner Geffray Mynshul written in 1618 he describes the temperament of an English prisoner “The character of a Prisoner. A Prisoner is an impatient Patient, lingering under the rough hands of a cruel Phisitian, his creditor having’caft his water knows his disease, and hath power to cure him, but takes more pleasure to kill him.”[8] Basically it points to one major aspect, debt. Much of prison life was worrying about your debt and how to pay it off. There were other types of prisoners but the system chaoticly and revolved around debtors.

There existed many different types of prisons. “Unlike today, the prisons were not all under one authority. There were several categories of prisons, distinguished from each other because of the nature of their ownership”.[9] First there were the national prisons. The Fleet and the Tower of London fell under this category. The next category was the country gaols. These “survived as the backbone of the prison system until 1877 when the central government took over all prisons”.[10] The third group was franchise and municipal prisons.

The Fleet Prison played a strong role in popular culture. “The most venerable of all English prisons was the Fleet which stood just outside Ludgate entrance to the city of London for eight hundred years”.[11] The prison stood at one of the entrances to the city. This is significant because of what people saw as they entered. The city of London had more people dying each year than were born. This meant there was a huge influx of immigrants. As many came to the city they had to walk by this prison. In the case of the Fleet it showed that the city had a great deal of crime and going to prison was a major aspect of living in London. It acted as a billboard advertising all the crime in the city.

The Fleet Prison also was a strong piece of a popular culture because of its association with the king. “It held a special position among English prisons, because it was ‘the King’s owne proper prison next in trust to his Tower of London, and as that is his fort in the east, soe was this one in the west of the city and chamber of his kingdome’”.[12] Because this prison was associated with the king it had much more weighted prominence. This also is a problem when analyzing life in prison. Because the Fleet has such a recognizable name it overshadows the main system of prisons, the country goals, this gives an off balance perspective of life in prison.

The best images of existence come from the inmates who wrote literature. As a distraction they wrote down accounts of their stay within. Importantly they analyzed the ultimate goal of being in prison. Joseph Hall wrote this piece. He was an early seventeenth century bishop. He also was educated at Emmanuel College thus making him part of the small sector of learned men in England. “Hall self-proclaimed himself to be the first English satirist.”[13] As a satirist he pokes fun at the system. This passage asks the two questions. The first is why one is in prison. The second asks why is there not another system in which prisoners are improved.

Thou art imprisoned; Wise men are wont in all actions and events to enquire still into the causes: Wherefore dost thou suffer? Is it for thy fault? Make thou thy Gaole Gods correction house for reforming of thy misdeeds: Remember and imitate Manasses, the evill sonne of a good Father, who upon true humiliation, by his just imprisonment, found an happy expiation of his horrible Idolatries, Murders, Witchcrafts, whose bonds brought him home to God, and himselfe.[14]

![]() He mentions a happy expiation being found. Basically a happy punishment is given to this prisoner Hall met. Failure is established. The prison system, Hall argues, makes a murderer more comfortable. He asks god for a more just system one in which the fallen ideologies of Bridewell are reinstated.

He mentions a happy expiation being found. Basically a happy punishment is given to this prisoner Hall met. Failure is established. The prison system, Hall argues, makes a murderer more comfortable. He asks god for a more just system one in which the fallen ideologies of Bridewell are reinstated.

Hall wants creditors to be paid. This signal of his obedience of the law shows how he wants one to be just and responsible. The following text continues his remarks of the system.

But if the hand of God have humbled and disabled thee, labour what thou canst to make thy peace with thy Creditors: If they will needs be cruel, look up with patience to the hand of that God who thinks fit to afflict thee with their unreasonableness[15]

Look up with patience is an explanation to his honorable tone about creditors. He knows they need to be paid for a just equilibrium to be found.

James E. Thomas examines ideologies of prisons. An important aspect of his work is the comparison of prisoners over the years.

“One of the tasks of this book will be to explore how far generalizations can be made about life in English prisons, and how far the same stresses and problems are evident at different times. Did the Criminal of 1543, the prisoner of war in 1643, and the debtor of 1743 all undergo what was essentially the same experience? The bond which connects all these disparate groups is that they were prisoners, not that they were criminals.”[16]

The last line is the key. Prisoners not criminals, the focus is how they were treated in the three different kinds of jails as well as what it was like to be a prisoner in this time period.

The staff of the prisons must be examined. They had a pivotal role because they complemented each prisoner as a guardian. “Bayliffs in general are a fort of destitute wretches made up of the dregs and refuge of mankind.”[17] This is a very strong message about the staff. The Bailiff controlled the life of the prisoner. There was a large problem with prison workers extorting prisoners. This primary source from 1699 helps illustrate how hated these workers were. Many prison workers were former prisoners and could be considered traitors by the prisoners. “The links between criminals and their custodians were closer than they are in our society. The gaolers themselves were often pardoned criminals.”[18] What this means is the Baliffs knew exactly what it was like to be a prisoner. This inside knowledge allowed them to use the prisoner to their full benefit. The author also points out his stance on the position of Bailiff. “Sir, I hope you will not mistake me; I am not Declaiming against or arraigning the Office of a Bayliff, but the persons that execute it.” This demonstrates that a prisoner of the time realized that the system was corrupt. Because he points out that the job itself is not bad in nature thus meaning that it is corrupted. The prisoner would therefore not respect the system because they know it is flawed.

The traits of the bailiffs are made apparent here. This piece tears apart the bailiff and showing how they lived a life almost as bad as the prisoners.

A COMMON CRUEL JAILOR

Is a creature mistaken in the making, for he should be a tiger; but the shape being thought too terrible, it is covered, and he wears the vizor of a man, yet retains the qualities of his former fierceness, currishness, and ravening. Of that red earth of which man was fashioned this piece was the basest, of the rubbish which was left and thrown by came this jailor; his descent is then more ancient, but more ignoble, for he comes of the race of those angels that fell with Lucifer from heaven, whither he never (or very hardly) returns. Of all his bunches of keys not one hath wards to open that door, for this jailor's soul stands not upon those two pillars that support heaven (justice and mercy), it rather sits upon those two footstools of hell, wrong and cruelty. He is a judge's slave, and a prisoner's his. In this they differ; he is a voluntary one, the other compelled. He is the hangman of the law with a lame hand, and if the law gave him all his limbs perfect he would strike those on whom he is glad to fawn. In fighting against a debtor he is a creditor's second, but observes not the laws of the _duello_; his play is foul, and on all base advantages…. That blessing is taken from them, and this curse comes in the stead, to be ever in fear and ever hated: what estate can be worse[19]

They were slaves to the system because of being stuck in the middle ground between the judges and prisoners. They carried out the dirty work and were hated the most of anyone. Because most had once been prisoners they now abused prisoners and were hated for being hypocrites.

Much of the writing from this period points to the flaws in the system. It was controlled by monetary value.

But official fees were only a part of what a new prisoner had to pay; there were many other exactions, mostly comprehended under the word ‘garnish’,which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as: ‘Money extorted from a new prisoner, either as a jailer’s fee, or as drink-money for other the other prisoners.’ Garnish appears to have been a universal prison custom.

In a turbulent world of different prisons this garnish links them all. This helps to uncover what a true prisoner was like. This link is important because the prisons may have operated differently but at the primeval level they all shared the greed for wealth.

The best primary source for life in prisons is the The Compters Common-wealth. Written by William Fennor, the famous playwright, in 1617 it explains life within the jail. “Thus have I beguiled the time, and I feare my self, in relating to you the true nature of the hole, the miserie of it; my defence to the slanderous objections, and the authoritie and justice of the Steward and the Twelve.”[20] Conditions in prison for many were as bad as Fennor explains. By using hole to describe the prison it leaves a cold dark image in our heads. But it should also be noted that this was not the condition for all prisoners. Therefore it can be inferred that Fennor is exaggerating a bit to make the reader more sympathetic to conditions. This does not mean that that most lived this way it just means that overall this was not the entire picture.

It stands out as a significant piece because it comes from the perspective of a man who spent time there. The book was written while he was in prison. “Fennor was arrested, at a suit, presumably, of the London Merchant whom he had so rashly knocked o’erthwart the plate.”[21] This work was a story between him and another inmate. It gives a first person look into the system. Interestingly enough Fennor’s piece starts with “It is enough to know, too much to see, that in the Computer there is roome for thee.”[22] This line shows that anyone can be in a prison. It is Fennor’s warning to the public at large that you best be careful. He did not think that he could be in a prison but has realized the terribleness of it. It is difficult in comparison to this time because now we have trials that are fairer. Back then you could be thrown in jail for anything like Fennor was without any fair process.

Within the following text the process Fennor went through is acknowledged and criticized. It must be noted this piece is more about political prisoners. Seeing that they too were prisoners is still a valid way to help examine the prisoner.

If it be a distructive practice to imprison free men without indictment or testimony of fact, committed by three witnesses, which the Law of the Kingdome requires. How comes it to passe that so many faithfull servants of God and the Kingdome, have been so long imprisoned, some a yeere, some two, some more; meerly for discharge of their duties to God and the Kingdome; in discovering the treasons and deceitfull practices of such as endeavoured the Kingdomes ruine; what makes Lilburne, Overton, Musgrave, Booth, and many more in the Tower, [H] Fleet, Newgate, Gate-house, VVhite-Lyon, every prison having some sufferers for the Kingdomes cause in it, who are high unto famishing; Oh England England, if thou suffer thy selfe thus to be enslaved by thy servants, thou wilt prove a bye-word to all Nations, and not deserve the pitty of any: Rouse up thy self, and rush upon thy adversaries; let them know that though thou hast been long patient, yet thou[23]

The idea that someone can be thrown into prison is looked down upon. This was an important aspect because it shows that the prison system was seen to be flawed during the time. It was easy for one to criticize after the fact. But this 1647 writer knew at the time that the system needed to be changed. Another vital line this the mention to the entire country of England being enslaved by servants and no Nation having pity. This statement shows that England treats its population in an unjust way and if not fixed this will lead to their downfall. England would be looked down upon by the rest of the world as a backwards land that lacks control of its country. The overall message was that England’s lack of concern for justice in the prison system shows a bigger picture. The country has a lack of care for all of mankind and therefore will result to the downfall of the country.

Dekker explains a lot about Newgate Prison. In this work the protagonist is a spirit named Cock Wat. It travels around the prison seeing what misdeeds the different prisoners did. This is a very useful tool for showing the different levels of prison life. The spirit, first, has the ability to go throughout the prison, which gives us good idea of the prisoners. Second, the spirit is not human and therefore gives less biased views about the prisoners. It acts as a neutral entity reporting on the true state of the Newgate Prison.

The introduction is a quick glance into the prison. The spirit reports on the state of the prison beds. This is important because it shows the different types of beds available which helps prove how there was so much variation from prisoner to prisoner.

When comming into the prison, I finde for seuerall offences, plenty of offenders, some lying on hard beds, but the most on harder bordes some with course and thinne couerings, the rest in of a barle, or other couer letterure, heauy Irons, some lawyers, some for walking on the padd, some hor mi, some foy, some stals, some letterglers, some morts some lettercoy Single, all cunning and cosoning quea and of all these they are, and their seuerall course of, in their due places[24]

Some beds are hard while others are harder. Some people have irons. They all are in their due places. This references different class levels. If you could afford a comfortable bed then you would go to your ‘due place’ and if not you would have a harder bed. The beds are contrasted by being hard and harder and not hard and soft because this is a prison. Even if a better bed could be afforded it did not change the fact that the prisoner is not free and therefore a bed theoretically could never be as good within the prison.

The spirit continues its journey through the prison going all about. It finally comes upon the prisoners and talks about the conditions of many of their faces and their overall life in Newgate.

such as by drunkennesse, haue made their bodies like dry fats, and their faces like a shriefes post of seuerall colours or swearers, whose oaths fly out at their mouths, like smoake out of a chimney, that deles all the way it passes, or lyers, and such commonly are theeues: for lying and stealing, or as inseperable companions, in sinfull society, as a and a receiuer, and indeede all sinners of what condition so euer, are at the sight of me, struck with a suddaine and violent remorce, reckon vp their liues, and make themselues Iudges of themselues in these offences, wherein their conscince giues timonie against them, that they are guilty, and present horror, they me in minde to the vpright Iustice and punishment which they know, long before this they haue deserued[25]

The prisoners are in dire conditions. Drinking excessive amounts of alcohol have left their bodies a mess. The phrase ‘dry fats’ shows that they are not just a fat waste but dead fat that has been sitting out. Prison has acted like the Sun in a sense and has aged and disfigured the prisoners.

Another important topic is the fact that the prisoners know they are sinners. In this sense the spirit almost acts much like the Grim Reaper. It comes and tells you of your fate. Dekker must have felt life in prison is a time of reflection. His work about the spirit reflects a god like creature judging the actions of the prisoners. Dekker must feel that most the prisoners were guilty and deserved some punishment. This evidence shows that the general conception was everyone in prison was guilty even if they were not. This contrasts greatly to the modern theory of being innocent until proven guilty.

Dekker looks down upon women in this work. Women are used to describe something evil here. They cause the prisoners to have even more pain. The spirit Cock Watt addresses them as being she creatures. It is not exactly obvious but the women appear to be prisoners as well as dragging their husbands deeper into debt. This duality of women showed that they were the scapegoats. They took the blame and life in prison for them must have been worse.

Yet shall it not be Impertinent, that I Cock Watt, your new discouerer, make euident, what vse these kinde of people draw from these she creatures, both abroad and in prison, first know, that your théees trauelling mort, is partly a setter of rob beries, partly a théefe her , but alwaies a receiuer of whats euer is and brought vnto her: for which fellonies, if him whom she cals her husand, chance to be apprehended, she tross in his businesse, labours his aduersarie to be good to him, & suffer him to be bayld ut, you shall want no teares, no knéelings, no intercessions, no perswasions, that it is the first fact that euer the poore man her bedfellow fell into, and will you ske his bloud, that he was neuer in prison before, and will you bee his doing, when if you but search the record at Newgate, you shll him to haue payd his garnish twentie times at least, but if it proue that at her Importunity you are mooued, and in pitty of her, spare her mates life[26]

The women caused much harm to the men in this passage. They keep the men stuck in a continuous loop. An important aspect is the garnish. Because of the women’s misdeeds the garnish is paid a number of times. This shows that misdeeds in the prison forced the garnish to go up. It also shows how the garnish was in every prison. It was the punishment for prisoners as well as the constant between all English prisons.

A prison that stands out among the rest is Bridewell. “Bridewell was a prison in London, England, that was completed in 1555. Houses of correction established in other English towns frequently used the name Bridewell as a generic title.”[27] What makes it different is its approach to prisoners. “Bridewell demonstrated how punishment assumes the dominant role against competing theories of correction, such as rehabilitation or vocational training.”[28] The betterment of the prisoner was the main idea. In all the other prisons it was just about holding them until they paid their debt or were executed.

The prison was copied all over. Because it was copied so much it shows that the prison contained new ideas that made prisons work better.

Bridewell was the mother of 200 descendants, and the principles it embodied were thought worthy of imitation in all parts of England by individuals and by institutions. ‘It proclaimed the gospel of labor, if it chastised with the thong or the rod, it also set prisoners to hard labor. Moreover, Bridewell sought to prevent crime and mendacity by taking children from the streets, and giving them a trade and an honest livelihood[29]

The most important prison of the entire time period, it proves that true imprisonment was not realized before its creation, proving Pugh is wrong. The Middle Ages did not have a system that tried to stop imprisonment.This picture here shows life within Bridewell. Although it is from the end of the seventeenth century it helps to see what it was like. The prison looks very disorganized. This appears to be an area for women. They are not wearing any kind of prison clothes. The man to the left looks as if he is the master. Behind him are gallows for punishment. It looks more like a bar than a prison. This all means that although Bridewell was a radical new place; although it still resembled other prisons. In theory it was original but in execution it was not much different.

The prisoners of Bridewell were the lower classes. Before this prison was created this class was left overlooked and doomed. They had no social mobility because to survive they had to steal and got stuck in a never-ending loop that put them in prison. Here they had more of a chance and could even make money.

Perhaps expressing the sentiments of the times tells us, ‘It is true that the prisoners in Bridewell belonged, as a rule, to the lower and even the vilest classes’. He identifies three classes of offenders at Bridewell: wastrels, unfortunates, and professional beggars. Such people were swept by the besoms and beadles and constables into Bridewell where they were set to work, and taught a trade. The governors clothed them, and so much per man or woman was sometimes paid by contractors[30]

Being able to make money was a change from other prisons were it cost money. This does not mean that garnishes did not exist in Bridewell. It means that there was an option that before had no been available and that was revolutionary. It was so revolutionary that it became the foundation to modern prisons.

Bridewell is significant not because it was the first prison but because it introduced a set of principles that were widely copied/adopted elsewhere. So much so, that some 200 English prisons and a few prisons in America became known as ‘Bridewell’s’. Author William Hinkle, in fact, argues that by its contributions to penology Bridewell was precursor to the modern penitentiary. In ways ironic, this may be so[31]

The reason Hinkle says this is ironic is because Bridewell’s intentions did not ultimately come to fruition. The new approach to prisons still was controlled by old methods. Rehabilitation is a lot of work. It costs a lot more money and there can be no corruption in the system because the guards must care about helping the prisoners get better. It is a lot easier to just punish someone. This is the case of Bridewell.

The lesson of Bridewell is that when policymakers and corrections administrations try to combine punishment with rehabilitative or therapeutic approaches, the punishment side of the program seems almost inevitably to maintain dominance[32]

The idea was a good one but the economics of it were not there. The punishment side was easier thus allowing it to be dominant.

The following two passages demonstrate the two different ideologies within Bridewell. The first explains its reforms. They were the reason Bridewell was revolutionary.

The penal reforms introduced by this institution had a widespread effect; a more humane treatment of petty offenders, the indeterminate sentence, the corrective influence of work, the industrial rehabilitation of the prisoner, even the idea of reformative treatment and of imprisonment were not established practices at the time[33]

The second passage describes why the revolutionary ideas were hard to use in practice. But ultimately is here to show how Bridewell still ravished prisoners within.

Punishment was a major component of the Bridewell system of prison discipline, employing many of the methods common in 16th and 17th Century Europe. Recipients of Bridewell discipline often brought suit or appeal in the Star Chamber for false imprisonment and abuse [34]

The punishment used ranged from various methods of torture. The methods varied widely, from starvation to forced confessions.

The different methods, such as having political prisoners in turrets, proves that this was a disorganized system just like the other prisons.

The following accounts come from various prisoners in Bridewell. I have selected a few from different chronological years so it paints a fuller picture of life in the prison. The first is a simple case that takes place in the same decade Bridewell was created. In it prison time is used as punishment.

Morgan Evans, the Servant of John Harrison Brewer, was brought into Bridewell on 26th day of April, 1559. Morgan lewdly and disobediently behaved himself unto the wife of his master, and put in peril of life by striking with a knife of his Master’s sons, and using other words of shameful and filthy report. Therefore he was committed to the close keeping of his house and should have been punished (whipped) for his offense but his Master intervened on his behalf and requested leniency. Morgan was released after four days promising that he would ask his Master for Forgiveness, and behave himself in the future[36]

The next passage shows how Bridewell was used as a holding area until execution just like the jails of the Middle Ages.

In 1584, Ralph Miller was examined in Bridewell with regard to some of the papal refugees in France. He appears to have spent some years in Bridewell, but was so respected and trusted that he was allowed to go in and out of prison, and was even on occasion trusted with the keys. He devoted much of his liberty to carrying food and money to his co-religionists in London prisons. ‘He loved nothing so much as convoying a proscribed priest to hungry souls who wanted bread. Quite illiterate, he had been a farm laborer near Winchester, and there he was executed in 1591. His seven children were brought up to the gallows to plead with him, but they could not shake his constancy. His ‘treason’ was that of early Christians, who refused to burn even a pinch of incense on a pagan alter[37]

So in this time prison could be both a holding place and for punishment. If you were respected you could leave the prison. The bracelet is much like the keys Ralph Miller was allowed to use to come and go. In both cases you can leave when the authorities allow it. So in his case the prison was just a way people could keep tabs on him until his execution.

The next passage is to help illuminate what it was like to sit in one of these prison cells. Even for a few hours is disgusting and many were in them for years. It is no wonder many wanted to just be executed.

1594- A religious prisoner of conscience, Richard Fullwood, wrote from a prison cell at Bridewell that, “His cell was narrow; it had thick walls; it had no bed in it and he had to sleep in a sitting posture perched on the window-ledge. For months he had not taken his clothes off. There was only a little straw in the place and it had been trodden flat, and now it was crawling with vermin and quite impossible to lie on. Worst of all, they left his excrement in an uncovered pail in that tiny cell, and the stink was suffocating. In these conditions he was waiting to be called out and examined under torture[38]

1594- A religious prisoner of conscience, Richard Fullwood, wrote from a prison cell at Bridewell that, “His cell was narrow; it had thick walls; it had no bed in it and he had to sleep in a sitting posture perched on the window-ledge. For months he had not taken his clothes off. There was only a little straw in the place and it had been trodden flat, and now it was crawling with vermin and quite impossible to lie on. Worst of all, they left his excrement in an uncovered pail in that tiny cell, and the stink was suffocating. In these conditions he was waiting to be called out and examined under torture[38]

It is hard to imagine sleeping next to your own excrement. This picture here is a model set up in the Clink Museum in London. It shows how many debtors lived. When these conditions are shown it makes the human side of the prison much more evident. Bridewell cannot truly be characterized as a better prison as it was just another hole in the wall for people to rot.

Prisoners sometimes became celebrities. During this time celebrities were not movie stars as they are today and celebrity status was only reserved for the elite. For a non elite to be a celebrity was rare and unusual. This rarity must have made them a bigger hit than any of the current elite. This is because they would stand out much better like a brighter star in the sky.

1646- Anna Trapnell suffered from acute mania and hysteria, In 1646 she began to see visions, and to hear the voice of God in human words. As long as she was regarded as a madwoman or a prophetess of the Most High, she was the sensation of the town. But, alas the day came when she had visions of the impending death of her protector- Cromwell. The prophetess of the Almighty was now a ‘dangerous imposter,’ who went up and down England, ‘deluding the people,’ and fomenting rebellion against the authority of parliament and the army. Accordingly, on June 2, 1654, the council committed her to Bridewell, no doubt expecting that the character of the prison and her disgust at her disreputable companions would quickly bring her to her senses. Unfortunately she became even more of a sensation and people swarmed from Blackfriars over the hump-backed bridge if only to catch a glimpse of the notorious Anna. The minutes of June 8, 1654, reflect that, ‘the officers have been much hindered in their duties by the great concourse of people resorting to her daily.’ The beadles must have found it difficult on Wednesday in early summer to force a passage for their prisoners (Wednesday was court day at Bridewell) through the noisy crowds[39]

People rushing to see this woman show that prisoners did not just have to be executed to be famous. They could have some other unique feature that intrigued many people.

Bridewell was a place of new ideas. “Bridewell’s significance lies in the underlying belief that something more than punishment was necessary.”[40] It had various different types of prisoners and conditions, yet still possessing the old ideas of the Middle Ages.

It came into being because of the rejection of negative penal measures alone as a solution to the problems presented by vagrancy, and the poverty and criminality which went with it. The founders wished to initiate a new attempt to reform. This is not to say that Bridewell was not punitive: it was very punitive indeed. By definition, any institution which restricts liberty is punitive[41]

The reason the prison did not ultimately get to enact its new ideas fully is because of problems at its creation. Edward VI, a huge supporter to the prison, died at a young age. His sister Mary I did not share his enthusiasm for the prison. She reestablished the old ideas of prison system after his death. Since these were added, the prison never had a chance to be fully independent of old methods.

Unfortunately, the spirit which underlay the foundation of Bridewell was not translated into practice. The first blow was the death of the young Edward on July 6th 1553, just under a month after a formal agreement had been signed between him and the City. Mary’s accession was disaster as far as Bridewell was concerned…Mary was hostile for a rather odd reason. She, and the Church, were rather embarrassed by the disclosures about the behaviour of immoral priests, which were extorted from whores and unfaithful wives in Bridewell’s whipping room[42]

Once the prison began both ideas were in place and impossible to separate. A comparison of food is a good way to show how far money got you within prison. “Bone of meat with brothe, Bone beef a pece, Veale roasted a loyne, Bread as much as they will eat, small beare and wine clared a quart”.[43] That is what the prisoners with money could get. This comes from a menu from 1592 that they were given. To show what a poor prisoner would get we look to this passage. “To fight and scramble for unsaverie Scraps, that come from unknowne hands, perhaps unwasht”.[44] The two meals once again fall on different end of the spectrum. Prisons were not equal in any regard.

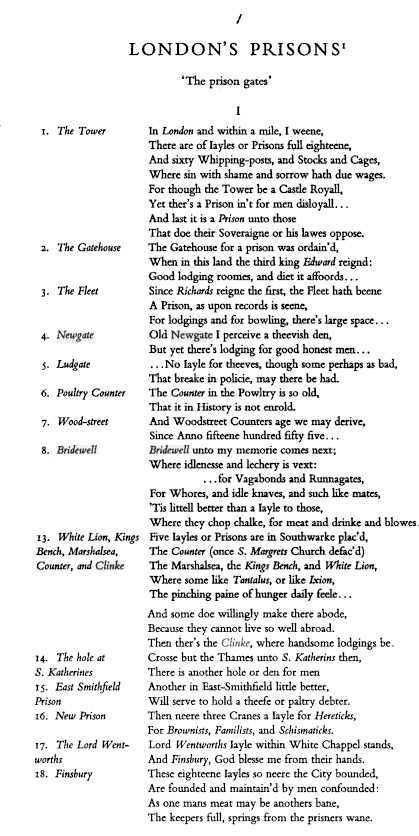

Another important piece of work is John Taylor’s 1623 pamphlet entitled The Praise and Vertue of a Jayle and Jaylers. In it all the prisons of that time are examined. He makes a list of all the prisons and it is pictured on this page. In it he mentions a total of eighteen prisons. For each prison a different sentence is used to describe how it is unique. This once again shows there was no one type of prison but more a multigrain assortment of prisons. Bridewell was mentioned as being slightly better than the rest. It helps show what the common view on these different prisons were. It also shows how complicated it was. If you were a prisoner and moved to a different prison it was a huge ordeal, rather like going to a different country. Because the prisons vary so much new ways of life must have be undertaken in each prison.

Prison conditions during the sixteenth and seventeenth century ranged all over the board. From poor people suffering in their own excrement to respected men who had keys to the prison and could come and go. Unlike prisons today, it was not a very uniformed place, people were incarcerated to pay back their crime with time. Individual prisons were so different that a list of individual characteristics had to be created. Prisons are not thought of as individual entities like this anymore. They are now a system.

The birth of a new type of prison occurred during this time period. Bridewell had revolutionary ideas. For the first time prisoners were tried to be improved. This system had many problems. The death of King Edward VI forced old methods to be continued within the prison. These ideologies were entrapped in the prison. The prison did show that a changing attitude was beginning for how prisoners were treated. Unfortunately it took many generations for torture to be truly taken out of this system, marking the beginning of a revolutionary idea.

The prisoners’ accounts of prison varied largely. The majority are debtors who are trapped due to having no money. They helped spread their tales through pamphlets. Without them the story of this time would be much more of a guessing game. Their stories show one main underlying theme. Economics controlled how their stay in prison would be. As long as the money held out, they could live peacefully in prison, almost as if they were staying in a hotel. Unfortunately many were poor and lived in filth. How horrific it must have been to sleep by your own feces for day or even years. The garnish paid, truly determined where on the spectrum your life in prison would be. Prison life was much like the outside world with respect to money.

How close the workers of the prison were with the prisoners also played an important part in life. They could make or break you in prison. In this respect prison resembles modern prisons in a way. If you are liked by the warden your stay can be paroled.

The Elizabethan Underworld out of all the texts it creates a very intricate portrayal of the prisoner’s life. The entire spectrum is looked up. It has a chapter to discuss how Bridewell differed and existed as a different type of prison. Overall it makes the most accurate listing of this time.

In regards to whether prisons were punitive or not is a hot issue. Scholars disagree on when this came into being. Some argue the middle ages were the birth of this idea. I argue that this idea may did not exist until Bridewell. People may have been kept in prisons for a long time but this was not punishment it was a means of collecting money from them or making sure they did not disappear. After Bridewell Prison was place where you were sent in order to be changed.

Prison life played a large role in the lives of the popular culture. Anna Trapnell became a celebrity because she was confined to a prison. People flocked to see her and were very interested in her ideas which had been banned by the government. Many other cases like this must have occurred. The ability to move freely in and out of the prison illustrate the access available to prisoners.

The prisons were not static. They were turbulent and changing. Conditions were terrible. However, life within the prison truly mirrored economic life outside the prison. The option existed to live like a king or a beggar. Money was the determining factor in this ability. Going into prison changed only your surroundings and not necessarily your station in life. Garnishes forced individuals to pay for all amenities. The ability, in some instances, to basically come and go from the prison, further illustrates the complexity of its society. Punishment, in many forms occurred within the prisons, however it did not solely define your stay in the prison as it does today. Money defined the form of the stay in prison. Prisoners were not necessarily criminals in this system, however, all prisoners were financially indebted. Money reigned supreme at the center of the prison universe during this period of history.

Works Cited

Bassett, Mary. The Fleet Prison in the Middle AgesThe University of Toronto Law

Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1944)

Bruccoli, Joseph. World Eras Vol. 1. New York. 1977.

Dekker, Thomas. Iests to make you merie with the coniuring vp of Cock VVatt, (the

walking spirit of Newgate) to tell tales. Vnto which is added, the miserie of a prison, and a prisoner. And a paradox in praise of serieants. Huntington Library and Art Gallery. 1607.

E.S. A Companion for Debtors and Prisoners, and advice to creditors in Ten. London. A.

Baldwin. 1699. pg B2

Fennor, William. The Compters Common-wealth. London 1619.

Hall, Joseph. The balm of Gilead, or, Comforts for the distressed, both morall and divine

most fit for these woful. London. 1646.

Hinkle, William G. A History of Bridewell Prison. Edwin Mellen Press. June 2006

Ireland, Richard W. Theory and Practice within the Medieval English Prison. The

American Journal of Legal History, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Jan., 1987)

Jokinen, Anniina,. “Joseph Hall.” Luminarium. 19 Sept 2006. [March 8 2008].

http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/hall.htm

Mynshul Geffray Essayes and Characters of a Prison and Prisoners. London. 1618.pg 8

Nicoll, Allardyce. Shakespeare Survey 17. Cambridge Press. Cambridge. 1964. pg 95

Pugh, Ralp B. Imprisonment in Medieval England. U.P. Cambridge. 1968.

Thomas, J. E. House of care : prisons and prisoners in England, 1500-1800. Nottingham,

1988. pg 6.

Salgado, Gamini, The Elizabethan Underworld. J.M Dent & Sons Ltd. Great Britian.

2005. pg 173

Various, Project Gutenberg's Character Writings of the 17th Century, accessed from

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10699/10699-8.txt

[1] By Various, Project Gutenberg's Character Writings of the 17th Century, accessed from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10699/10699-8.txt

[2] By Various, Project Gutenberg's Character Writings

[3] Allardyce Nicoll, Shakespeare Survey 17. Cambridge Press. Cambridge. 1964. pg 95

[4] Ralp B. Pugh Imprisonment in Medieval England. U.P. Cambridge. 1968. pg 1

[5] Richard W. Ireland Theory and Practice within the Medieval English Prison. The American Journal of Legal History, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Jan., 1987)Pg 57

[6] William G. Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison. Edwin Mellen Press. June 2006. pg 189

[7] Gamini Salgado, The Elizabethan Underworld. J.M Dent & Sons Ltd. Great Britian. 2005. pg 173

[8] Geffray Mynshul Essayes and Characters of a Prison and Prisoners. London. 1618.pg 8

[9] J. E. Thomas, House of care : prisons and prisoners in England, 1500-1800. Nottingham, 1988. pg 6.

[10] Thomas House of Care pg 6

[11] Mary Bassett The Fleet Prison in the Middle AgesThe University of Toronto Law Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1944)pg 383

[12] Bassett The Fleet Prison in the Middle Ages pg 383

[13] Anniina Jokinen,. “Joseph Hall.” Luminarium. 19 Sept 2006. [March 8 2008]. <http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/hall.htm>

[14] Joseph Hall The balm of Gilead, or, Comforts for the distressed, both morall and divine most fit for these woful. Pg 6

[15] Joseph Hall The balm of Gilead, or, Comforts for the distressed, both morall and divine most fit for these woful times Pg 7

[16] Thomas House of Care pg 5

[17] E.S. A Companion for Debtors and Prisoners, and advice to creditors in Ten. London. A. Baldwin. 1699. pg B2

[18] Salgado The Elizabethan Underworld pg 189

[19] By Various, Project Gutenberg's Character Writings

[20] William Fennor The Compters Common-wealth. London 1619.pg 46

[21] Salgado The Elizabethan Underworld pg 174

[22] Fennor The Compters Common-wealth pg 46

[23] J.H. The Antipodes, or Reformation with the heales upward pg 6

[24] Thomas Dekker Iests to make you merie with the coniuring vp of Cock VVatt, (the walking spirit of Newgate) to tell tales. Vnto which is added, the miserie of a prison, and a prisoner. And a paradox in praise of serieants. Huntington Library and Art Gallery. 1607. Pg 29.

[25] Dekker, Lests to make you merie… pg 25.

[26] Dekker, Lests to make you merie… pg 28.

[27] Joseph Bruccoli World Eras Vol. 1. New York. 1977.pg 240

[28] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg V

[29] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 231

[30] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 111

[31] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg ii

[32] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg x

[33] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 188

[34] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 188

[35] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 196

[36] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 191

[37] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 193

[38] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 193

[39] Hinkle A History of Bridewell Prison pg 195

[40] Thomas House of Care pg 168

[41] Thomas House of Care pg 168

[42] Thomas House of Care pg 169

[43] Nicoll, Shakespeare Survey 17. pg 90.

[44] Nicoll, Shakespeare Survey 17. Pg 90.